Welcome. This website introduces my work and my friends. Because the two are connected.

My work, since 1978, has been in the field of employee ownership. That work takes place through companies owned in part or in full by employees through Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOP’s) and through Employee Ownership Trusts (EOT’s) and Cooperatives. The focus of my consulting work in this field has been on “after the transaction” training and education efforts within firms. Details about consulting that my colleagues and I perform in this field can be found at the web site of the company my partners and I founded in 1987, Ownership Associates. I also serve as a Special Advisor to American Working Capital, a merchant banking firm with a specialty in the field of employee ownership.

In addition to consulting, I serve as a Carey Fellow at the Rutgers Institute for Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing and as a Lecturer teaching full semester courses on this topic. I also write both for scholarly and popular outlets. Examples of recent journalism can be found below. Further down, a video of a lecture at the Harvard Law School Forum entitled Building Workplace Democracy: The Employee Equity Loan Act. A full listing of articles and media can be found under the Published Articles tab in the site’s menu.

-

Are you sure?

-

"Cousin" Christopher Lydon, WBUR Open Source Radio

-

Legal Eagle, former Colleague and Man About Town: Clark Arrington

-

Fashion Advisor, Robert "Bobby' Buchele

-

Next Generation Ownership Associates? Takeover Artists Aniqa Moinuddin and Kyla Alterman, March, 2019

-

Barry White (a/k/a Omar Abdul-Malik) and Christopher Mackin, DC, 2019

-

Reunion of the Ancients, November, 2019 Cambridge, MA

Founders (1978) of the Industrial Cooperative Association

From Left: Steve Dawson, David Ellerman and Chris Mackin

-

Steps of Baker Library, Harvard Business School

Where, on June 4, 1927 - Owen D. Young, Chairman of General Electric called for an economy where there should be "no hired men."

-

Dick May, David Ellerman in front of UMASS Cambridge (a/k/a Harvard)

-

Tough Love Training with Tej Gonza, Institute for Economic Democracy, Ljubljana, Slovenia

-

What?

-

Impressionable Young Swede Visits San Diego - June, 2019 - Patrick Witkowsky, Producer/Director of Can We Do It Ourselves?: A Film About Economic Democracy

-

Chicago ESOP Mafia - Dick May and Jerry Kaplan

-

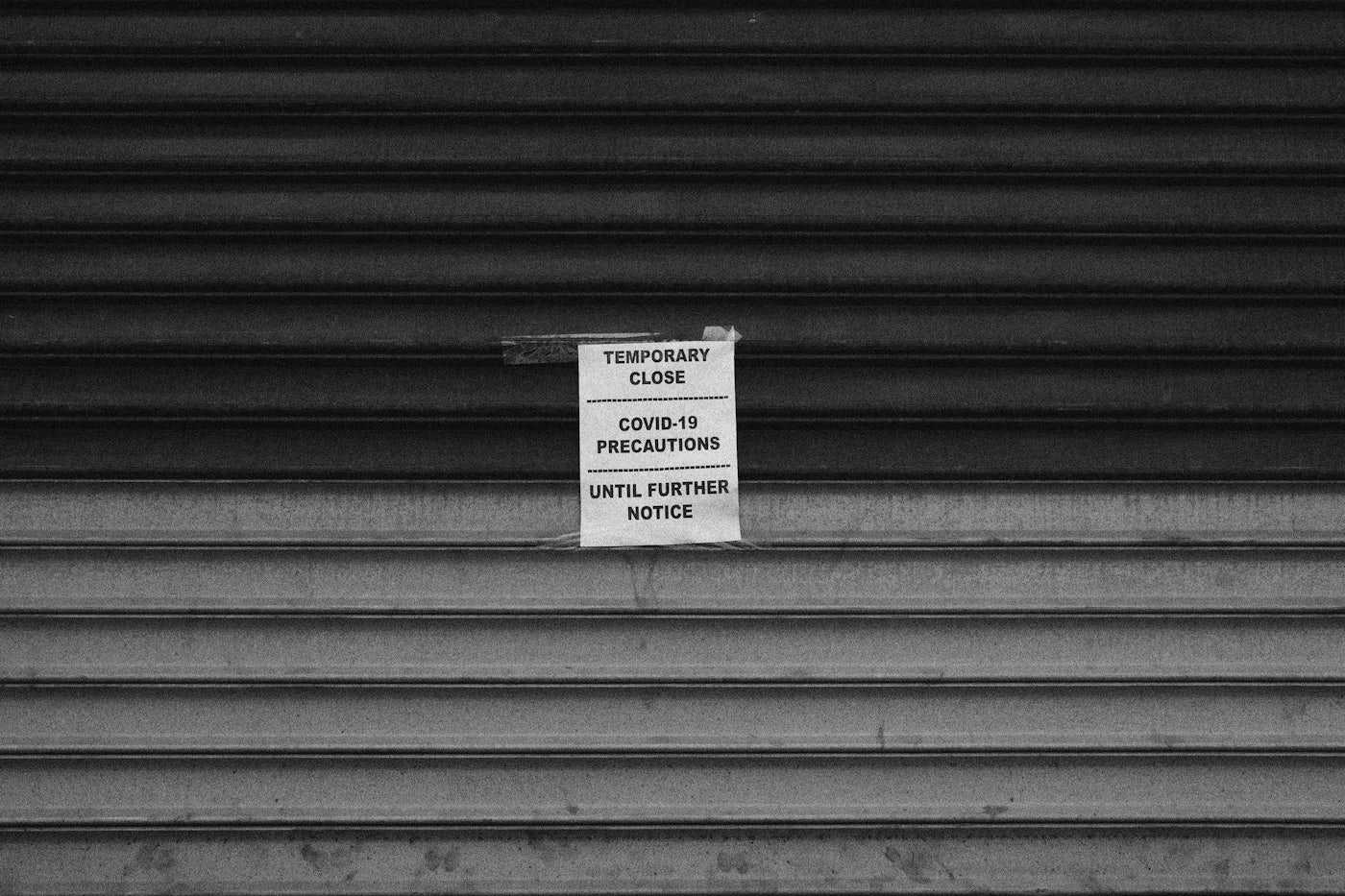

A Pandemic Dividend for Every American, The New Republic, 1/1/2021 - Read on The New Republic.

A Pandemic Dividend for Every American

All citizens deserve a share of the wealth that’s being disbursed to save the economy from Covid-19’s ravages.

SPENCER PLATT/GETTY

SPENCER PLATT/GETTYWith vaccinations underway and the Biden administration about to assume power, attention will soon return to an assessment of the true damage that Covid-19 has wreaked on the American economy. At this moment, it’s important to take stock of the various rescue measures that have been extended by the federal government and consider how they should be amended in the future. Above and beyond the $900 billion stimulus recently signed by President Trump, over the next two to four years it is likely that between $5 to $10 trillion dollars of taxpayer money, in the form of taxpayer-backed loans and loan guarantees, will be expended to save American businesses and jobs. That level of government aid, the largest on record in American history, will likely require more than a generation of productive effort to pay back. A reckoning with the government’s role in rescuing the economy in this fashion also creates an opportunity to pose some of the larger questions about productivity, fairness, and economic inequality that preceded the pandemic.

The preservation of employment, and the need to ensure that those vital paychecks that sustain workers and their families keep getting cut, has been foremost in the minds of policymakers during the pandemic. Presuming taxpayer-provided funds and guarantees will continue to play a key role in the recovery of private sector employers, incumbent shareholders should not be the sole beneficiaries of recovered value. Instead, it should be shared with employees working at all levels of each firm receiving assistance and with each and every citizen whose tax dollars are the ultimate source of funds for the recovery.

The financial crisis of 2007-2009 provides a useful precedent. Much has been written about how the largely “hands off” terms of the $500 billion distributed through the Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, served as a windfall for financial institutions. One positive exception to that approach took place in the automobile industry. In 2008, the White House Council on Automotive Communities and Workers orchestrated negotiations among unions, management, and the federal government, which resulted in the creation of a Voluntary Employee Benefit Association, or VEBA, named the Detroit Automakers Retiree Medical Benefits Trust. In exchange for $80 billion dollars of TARP funding, this trust held large shareholding stakes at General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler Corporation that eventually recovered significant economic value for the federal government. Earnings from those shares, recently valued at $56 billion, continue to meet the health care expenses of auto workers at those companies.

The Covid-19 crisis of 2020 and beyond is arguably broader and deeper than the 2007 financial crisis. It should therefore employ longer term and broader recovery strategies. If taxpayer dollars are fueling the recovery of private sector firms in particular, then fairness demands that all American citizens should share in the future benefits of that recovery. Two mechanisms can be enlisted to achieve that goal.

The first mechanism should be the introduction of legal trusts that can hold shares of stock in the firms receiving federal loans or guarantees. Those trusts would hold shares on behalf of employees at all levels of these firms, not just senior executives. When recovery occurs, all employees will share in the upside.

Over 40 years of federal tax policy promoting Employee Stock Ownership Plans, or ESOPs, has built a track record for this idea. Research evidence supports the claim that employee ownership makes a positive difference in the productivity, profitability, and longevity of firms. The economic advantages of participation in ownership for ordinary workers are substantial. A Kellogg Foundation-funded study conducted by Rutgers University found that workers enjoyed retirement benefits three to five times larger than those without an ownership stake.

There are signs that policymakers on both sides of the political aisle see the promise of these ideas in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. In July, a bill called the Temporary Federal ESOP Grant Program Act of 2020 was introduced by Republican Senator Ron Johnson and cosponsored by Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin. It proposes that the federal government extend grants to companies of $20,000 per employee in exchange for the establishment of an ESOP plan. If successfully attached to future rounds of pandemic-related federal assistance to the private sector, this measure will introduce the principle of a more inclusive and shared economic recovery.

The merits of these ideas in the current moment have penetrated beyond Congress. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban also weighed in on Twitter and in subsequent interviews, stating, “If we are going to bail out companies, we need to make sure all employees benefit from a turnaround, not just executives. This would be a step toward income equality.”

Beyond employees and executives, taxpayers also deserve a return of their principal and a share of any potential upside. Many Americans employed in the gig economy and elsewhere do not enjoy employee status in scaled money-making organizations. They too should be enfranchised and rewarded through structures such as the National Wealth Fund concept described by Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth. Such a fund should also receive an allocation of shares from firms receiving substantial loans or guarantees from the federal government. Depending on firm performance, those shares would produce an annual yield distributed directly to every citizen.

The idea of including citizens in the wealth stream made possible by public investments is, in turn, related to a myriad of proposals for universal basic income popularized by Andrew Yang, Andy Stern, and Peter Barnes. Those ideas source their funds from either the public treasury or, in the case of the Alaskan Permanent Fund and other funds described by Barnes, from a fraction of the earnings that private entities extract from exploiting common environmental assets. Ideas in this vein are on the horizon. The immediate crisis, however, involves the need for a public quid pro quo to establish what conditions, if any, should be attached to the disbursement of unprecedented amounts of taxpayer dollars to rescue private sector firms during the Covid-19 crisis.

We propose that any future Covid-19 related federal assistance to private sector firms should be allocated among three groups: existing shareholders, employee trusts, and a National Wealth Fund. Specific allocations should be calculated by determining the fair market value of governmental infusions of cash and loan guarantees as a percentage of the fair market value of individual firms. Because employee trusts represent internal agents—employees—whose motivation and concrete efforts will significantly determine the likelihood of business success, they should be proportionally favored over a National Wealth Fund in the allocation of shares.

Whether the starting point of economic policy discussions is the present Covid-19 emergency or the perennial topic of economic inequality that preceded it, strategies that rely upon wages alone will not get the job done. In addition to income, wealth creation must be shared. Federal economic programs that support the private sector today such as the Export-Import Bank mostly offer trickle-down rewards for workers. When those programs succeed, jobs may be preserved or even expanded. But the truly significant long-term economic benefits the government makes possible accrue to a narrow group of shareholders.

The best way to improve on conventional policy designs is by enabling broad-based ownership. The Federal Home Loan Act of 1932, or FHLA, was perhaps the most radical federal policy intervention of the twentieth century. The FHLA and the bills that followed it put the borrowing power of the federal government at the service of ordinary American workers. That assistance took the form of loan guarantees, which convinced lenders that millions of relatively low-net-worth borrowers should receive home mortgages.

This same principle can be extended to the private sector economy today. The proposed Employee Equity Loan Act, or EELA, would extend federal loan guarantees to employee trusts that could buy out retiring owners of the tens of thousands of privately held firms that will change hands today and in the near future. Instead of selling those businesses to private equity firms who further concentrate wealth, business owners can sell to the people inside the four walls of their business whose labor helped them succeed in the first place.

Ideas such as these require both individual and institutional champions. At the federal level, the Department of Commerce has long served the interests of American business owners. The constituency that agency serves needs to be expanded to include American workers. A reinvigorated Commerce Department would be the logical host for ideas such as employee ownership and the oversight of a National Wealth Fund.

The Covid-19 pandemic has tested the nation’s resolve, but the manner in which we knit the nation back together from its ravages should not rely on policies that preserve and potentially compound existing inequalities. By expanding upon ideas that enjoy some measure of bipartisan support and bring previously excluded groups to the table, we can navigate our way through to the end of the crisis stronger than how we entered it. And by cutting in workers, as well as ordinary taxpayers, into the long-term benefits of the investments we make to save our economy, we can preview the emergence of a more inclusive and dynamic brand of American capitalis

-

Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis, Public Policy and Corporate Governance Implications, Challenge Magazine, June 1, 2020 - Read on Challenge Magazine

Introduction

Our societal response to the COVID19 crisis should be guided by basic moral principles and economic common sense. This essay will explore five essential steps or programs that suggest how we might navigate forward while we reckon with the root causes of this crisis, some of which can be found in nature and others in our flawed but reformable social and economic institutions.

The first principle which should largely be delegated to journalists, scientists, lawyers and the courts is justice. We must determine who is at fault for this crisis, and the extent to which it was preventable or could have been better mitigated. While stressing the priority of prevention against further, imminent crises that lay ahead, we must also reckon with responsibility for what has transpired. We must establish who has been damaged and how they can be best helped. We must prioritize how health can be restored and maintained, how families can be protected and how schools, police, fire and other public services can be safely restored. We must then turn to how we can provide rational assistance to economic institutions, to businesses and organizations, small and large, for-profit and nonprofit, public and private.

A second principle that must be applied to recovery from the COVID-19 crisis is fairness. We need solutions that protect the least resourced of our citizens, those most in need. Those middle- and upper-class members of American society most secure in knowledge and wealth will get by though their knowledge or through their wealth. Government should prioritize the most vulnerable of our citizens in need and work its way up over time toward providing assistance to working-and middle-class citizens.1

Large Business Organizations – Publicly Traded

Large organizations with highly skilled leadership and work forces backed by sophisticated advisors and wealthy owners that find themselves in need of government backed support should be held accountable and must be changed by this COVID-19 crisis. Corporate governance in particular should be changed and shareholders should suffer the market’s accounting for the lack of ability of their existing Boards, managers and advisors to be able to foresee or better react to this crisis. Our larger, publicly traded companies at risk of bankruptcy will only be improved if government relief is conditioned upon structural changes in equity ownership and governing control.

The primary structural change these companies should implement will involve the creation of long-term allocations to enterprise level profit sharing trusts. Those trusts should target a significant percentage of stock of each company, estimated to be between 10–30% of outstanding stock, and be held in perpetuity for its employees. Perpetuity should be created through mechanisms that replenish future redeemed shares to maintain a minimum significant stake for its US citizen employees.2 Accompanying the creation of those trusts, new, expert and independent Board representation should also be installed. The choice of new Board representatives should take place in consultation with employees in affected companies and independent advisors.

United States Sovereign Wealth Fund

Government invested funds of large publicly traded companies in excess of the 10–30% value of outstanding stock, allocated to employees, should be contributed to a newly designed United States Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF). Examples of such funds include the Government Pension Fund of Norway or the Alaskan Permanent Fund.3 A new American SWF should be a federally chartered institution whose sole fiduciary duty would be to promote the financial welfare of US citizens.4 No distributions of principal out of the SWF would be allowed. The asset base of such an SWF would be maintained in perpetuity for future generations. Citizens would receive an annual check consisting solely of dividends, earned interest and rents derived from the assets held by the SWF.5

In addition to the SWF being the repository of asset holdings accumulated through the extension of government credit during the COVID-19 crisis, a new American SWF should also become the repository of the financial value of assets that comprise the American natural resource commons. Examples of assets that would comprise the commons post the Covid-19 pandemic could include fees, rents and royalties for use of publicly owned lands, water contained in federally owned lakes, rivers and aquifers and coastal properties bordering our oceans. Other commons assets could include carbon credits for clean air, certain patents and copyrights on knowledge produced by government funded research, the market value of electro-magnetic spectrum that enables wireless technology and air, sea and automotive traffic control. Earnings from the use of those assets held by the SWF would be distributed annually on an equal basis to all United States citizens.6

Small Privately Held Companies

The needs of smaller privately held companies of less than 500 employees are the most acute in the American economy. These firms have a lower institutional value than larger public firms, with less in-depth management and a larger base of employees with little or no accumulated wealth. The pandemic caused unemployment in this sector creates large and unsustainable unemployment benefit liabilities for local and state governments. These companies provide 50 plus percent of American jobs and most of American job growth. They also supply most of our country’s technological innovation and are the incubators of America’s future economic potential.

Loans to these firms should be underwritten on an expected company enterprise value based upon their pre pandemic financial performance. Loans should have equity components but this equity should be directed into a profit and wealth sharing trust for the benefit of their employees’ retirement savings. These trusts should hold stock targeted at a minimum of 30 percent of the outstanding stock of these companies. That stock can be supplied either through new issues of stock from company treasury’s or through the purchase of stock from existing owners.

Taking into account particular circumstances effecting smaller firms, accompanying the creation of those profit sharing trusts, new, expert and independent Board representation should be installed. The choice of new Board representatives should take place in consultation with the affected company’s employees and outside advisors.7 Employees should receive mandated profit and wealth sharing payments to maintain the target 30 percent ownership interest from rescued businesses on an annual basis in addition to upon leaving or retirement.

Loan underwriting requirements and the design of each profit and wealth sharing trust can be driven off each company’s audited financials, tax returns and payroll tax filings. In order to not delay the immediate deployment of funds, a provision in the government loan agreements should require that these profit-sharing trusts be set up and contributed to within one year of the loan’s funding. Government loans to this sector should include a loan forgiveness set aside to cover the costs of establishing these proposed profit-sharing trusts.

United States Federal Revenue Sharing

Most if not all state, county, city, town and village governments will be facing immediate funding needs because of diminished sales and property taxes and large unemployment consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Because the Federal government is the most efficient source of immediate capital with unlimited borrowing capacity, taxing authority and the technical capacity to evaluate need, it should immediately reinstitute the Nixon-era Federal Revenue Sharing program for the benefit of these critically important State and local government agencies.

Revenue sharing should be considered as part of the citizens share and Sovereign Wealth Fund ideas previously described. Revenue sharing should be instituted before economic damage caused by COVID-19 is visited upon to these essential governmental entities. Without immediate action, this need will cascade into a total municipal local state, county, city and village bond meltdown effecting the essential services of police, fire, water, waste removal, schools and parks that these government agencies provide to all US citizens. It must be instituted as soon as is practically possible.

Citizens Reconstruction Corporation

The federal government should establish a Citizen’s Reconstruction Corporation (CRC) to help absorb the surge in unemployment that will follow from the COVID-19 crisis and its aftershock which will be historic and perhaps long term.

The CRC should provide immediate living wage employment opportunities. It should be administered through a two-year employment and service initiative organized as a public/private effort across all states. Specific projects that would be serviced by a CRC would include:

-

Military and National Guard support as needed

-

Peace Corps

-

AmeriCorps – service to lower income communities including teaching

-

HealthCorps – providing future doctors nurses medical school credit

-

ConservationCorps – in conjunction with larger climate remediation projects such as a Green New Deal, restoring and in some cases building new parks and recreational centers in, cities, rural towns

-

TradeCorps – Job and skill training and apprenticeship work in building trades and service careers organized as a public/private cooperative

Participants completing two-year service requirements in the above CRC programs would be entitled a two-year education and training grant to pay tuition, books and living expenses at qualifying universities, collages and trades training schools. Federal resources directed to CRC projects will fully subsidize the cost of tuition, books and housing for public, community college and related training institutions. Graduates of these programs will secure a first claim on new employment offered by businesses receiving government support for up to ten years.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has prompted the federal government of the United States to provide a lifeline to private sector employers ranging from our largest publicly-traded firms, to firms financed by private equity, to the modestly sized firms of Main Street. Intervention at each of these levels is warranted but should be carried out with discretion and only after an examination of the underlying strengths of each firm. Government assistance should be tethered to a quid pro quo that begins to change the underlying dynamics of corporate governance and wealth sharing through ownership in the United States. Rather than resort to government ownership and the suggestions of socialism that would inevitably accompany that path, we argue that employees should be the primary holders and beneficiaries of government extended funds. It is the employees, serving at all levels of a workplace from the shopfloor, to technical workers to senior management that should serve as proxies for the public interest, the public funds being extended in this emergency to help rescue our economy. The scale of this crisis is unprecedented and extends beyond our private sector. For this reason we also urge a revival of ideas selected from both a conservative heritage; the Federal Revenue Sharing models first considered during the Nixon administration and a progressive heritage, a Citizens Reconstruction Corporation that can promote nationwide, large scale employment and training efforts animated by the aspirations of a Green New Deal.

Additional information

Notes

1 Further moral and historical arguments in support of these ideas can be found in an essay Toward an Economic Democracy, published by Christopher Mackin in The New Republic magazine March 25, 2020.

2 It should be noted that many publicly traded US companies have substantial non-US citizen shareholders who should not be beneficiaries of recovery efforts initiated by the US government.

3 Information here describing the Government Pension Fund of Norway. Information here describing the Alaskan Permanent Fund.

4 Eric Lonergan and Mark Blyth provide a useful sketch for such a fund in a March 2020 discussion paper for the Institute for Public Policy Research in the UK. The title of this paper is Beyond Buyouts.

5 An alternative structure to the Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) design worthy of further consideration would involve the creation of a new National Recovery Board of the federal government structured along the lines of the Federal Reserve Board but with a mandate to focus on private sector recovery initiatives.

6 Peter Barnes has made a compelling case for a natural resource “commons” based Fund in his 2014 book With Liberty and Dividends for All: How to Save Our Middle Class When Our Jobs Don’t Pay Enough

7 Private firms with under 100 employees would be encouraged to establish Boards of Directors with independent outside members in consultation with employees and outside experts. These firms may prefer the use of Cooperative legal structures. Private firms with over 100 employees should establish Boards of Directors with independent and expert representation selected in consultation with employees and outside advisors.

-

-

Toward an Economic Democracy, The New Republic, March 25, 2020 - Read on The New Republic

Toward an Economic Democracy

Why the coronavirus crisis is an opportunity to reshape the relationship between workers and their employers

SPENCER PLATT/GETTY IMAGES

The most fundamental tragedy of the coronavirus crisis is human. It is lives being lost. Somewhere close behind is the feeling of desperation shared by working people. In an economy where it is estimated that 50 percent of the labor force survives from paycheck to paycheck, we are facing an economic crisis of unprecedented proportions that exposes a fundamental flaw in our widely accepted idea of the relationship between working people and their places of work.

That fundamental flaw is a long-standing acceptance across the ideological spectrum of a division between wage earners and the owners of capital assets. While owners of businesses are able to fall back on accumulated wealth and assets in a crisis, it has become abundantly clear that a majority of workers are prisoners of wage income. As long as that divide persists, the threat of economic breakdown will loom both in the coming months and into the next crisis. That divide is the heart of economic inequality. Near-term measures that maintain or increase wage income should be implemented. But it is time to think more deeply about the causes of inequality, and it is time to introduce remedies that serve as conditions for the provision of federal government assistance.

As Mark Cuban, owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, has wisely counseled, no governmental interventions now being considered should be entered into without consideration of how that intervention will address inequality.

A prominent test case—the airline industry—can help lead the way. Any federal funds loaned to the airlines should be repaid in two steps. The first dollar repaid should be directed to newly established Employee Stock Ownership Plans, or ESOPs, at each company whose beneficiaries are the more than 500,000 airline workers, from luggage handlers and flight attendants to mechanics and pilots. The second dollar repaid should return directly to the federal government. Using that formula, over a short period of time, employees will accrue a substantial stake in these companies. They or their selected professional representatives should serve prominently on company boards of directors to give voice to the employees that make the business work.

As Columbia law professor Tim Wu points out, the American public also deserves corporate governance representation to help steer the airlines back to responsible stewardship. Narrowly focused stock buybacks in public companies that have enriched a small set of the corporation’s stakeholders, senior management, and quick-flipping, short-term shareholders should end. If management balks, they should be educated on how this arrangement is a superior corporate model for workers, shareholders, and the public. There is abundant empirical evidence that it is. It simply requires more of management.

A second mechanism to use with the airlines and with any other private-sector company receiving governmental support can also speed up the process toward greater wealth participation by ordinary working people. Business taxes should be rethought. They should be paid in full if they perpetuate status quo arrangements that keep workers on the outside of ownership. A necessary reform would simplify existing rules by crediting a company’s tax payments dollar for dollar against its federal tax obligations. Payments that would ordinarily be directed to the federal government should instead be directed to purchase company stock that would be held by trusts for company employees. Over time, working people would become substantial owners of the companies they work for and enjoy a voice and a share in the wealth they have helped create.

The idea of restructuring our economy so that capital is a resource that works for labor and not just for itself is not a new one. Workers didn’t always work solely for wages. They used to work in small shops and on farms. In the middle of the nineteenth century, as industrialization was taking hold, some labor leaders warned that an employer-employee relationship where the first group owned and the second group was expected to survive on wages was a trap that would result in dependence and servility. They argued for employee ownership of the newly emerging industrial economy as an alternative where labor should work for both wages and capital ownership.

Strangely enough, so did a smattering of legendary industrialists, including Robert Brookings, Leland Stanford, and, early in the twentieth century, the chairman of the General Electric Corporation, Owen D. Young. On July 4, 1927, Young took the podium on the newly installed granite steps of the Baker Library at the Harvard Business School. He was the guest speaker for the opening of that grand building, and he had a surprise vision to share with the audience. He asked his audience to consider whether American capitalism, then barely a century old in its industrial form, had been launched on the right foot.

Into these [larger-scale businesses] we have brought together larger amounts of capital and larger numbers of workers than existed in cities once thought great. We have been put to it, however, to discover the true principles which should govern their relations. From one point of view, they were partners in a common enterprise. From another they were enemies fighting for the spoils of their common achievement.

He spoke hopefully that the Harvard Business School might be a place where his alternative vision could be fleshed out and made to work.

Perhaps someday we may be able to organize human beings engaged in a particular undertaking so that they truly will be the employer buying capital as a commodity in the market at the lowest price.… I hope the day may come when these great business organizations will truly belong to the men who are giving their lives and their efforts to them, I care not in what capacity.… Then we shall dispose once and for all, of the charge that in industry organizations are autocratic and not democratic.… Then, in a word, men will be as free in cooperative undertakings and subject only to the same limitations and chances as men in individual businesses. Then we shall have no hired men. That objective may be a long way off, but it is worthy to engage the research and efforts of the Harvard School of Business.

It takes a crisis of the magnitude of the coronavirus to reveal to us how poorly designed the dominant U.S. corporate economic arrangements are from the point of view of sharing the common wealth all workers help create. There are alternative wealth-sharing arrangements to the dominant U.S. corporate structure that are within reach. Some of them, like the 7,000 companies across the U.S. that are owned by their employees through ESOPs, have survived and prospered on the margins of this dominant structure. It is time to expand the reach of these ideas to the commanding heights of the American economy in order to design an inclusive form of capitalism that ends the utter dependence of most working people on their weekly paycheck.

The wealthy in America are disturbed by the coronavirus crisis, but they can sleep at night knowing that they have reserves that can get them through these difficult times. It is now painfully evident at this moment that that same comfort of having stored up wealth through your life’s work must be an opportunity extended to the rest of working America.

Finally, we need to appreciate that this is a root-and-branch moment. Owen Young is not the only neglected prophet whose stock is rising. Visionaries and critics who have warned about the dangers of unchecked economic growth, industrial agriculture, and remote supply chains must get a new hearing. Private patents on life-saving technologies should be terminated. Stock buybacks limited to grasping senior managements should be officially over.

But an economy where workplaces are comprised of fellow owners, where there are “no hired men,” can still sound, at this acute moment of crisis, like a special pleading. What about all of those outside the reach of the workplace? How are these ideas going to help them?

The best answers to that challenge are partial. And while there are concrete advances that should follow from reengineering the ownership and governance of the modern workplace, the responses on offer are also necessarily abstract. Perhaps the broadest claim that can be made in favor of these reforms is that the vitality and the moral responsibility of an economy is the single best guarantee that society can extend to all of its members. The economy is what will make and deliver their resources, food, shelter, health, and technology. It is where our problems will be solved or allowed to fester.

The reigning, now staggering, modern structures of economic life have arguably delivered on something we can narrowly describe as vitality. Technology has achieved wonders. Increases in productivity have reduced poverty. But modern economic life has also become significantly unmoored from responsibility to people and the planet. There is not only a coronavirus loose upon the land. When inequality is allowed to reach the unprecedented heights that prevail today, we are also confronting a historic responsibility deficit that traces back to a lack of accountability, a lack of democracy, in our economic institutions.

Unless we are going to fall for an even more romantic and already historically discredited idea of government ownership, a “do-over” for the socialism of the twentieth century, we can hope and reasonably expect that workplaces that are governed from within, not by the state but by their workers, engineers, and managers, will lead to a more responsible economy. That is economic democracy, the long-neglected complement to political democracy. It is not socialism.

And what standards of social responsibility might we expect from firms that are owned and governed democratically? Workers are also citizens. They drink the same water that consumers in their communities drink. They are not absentee investors, buying and selling their stock in nanoseconds. It seems reasonable to bet that if given the chance, they and their counterparts in management can be counted upon to arrive at answers about how best to carry out our economic life far better than the impersonal stewards of modern finance. The regulatory power of the state would not disappear under economic democracy. It would remain as the vigilant protector of the public interest. But for democracy to live up to its potential in society at large, the realms of the polity and the economy must remain distinct and in constructive tension.

Exactly 20 years ago, in a neglected book called Democracy at Risk, attorney Jeff Gates coined a metaphor that aptly described the “maximizing shareholder value” framework that has served as the conceptual North Star for elite opinion and for our business and law schools across the land. Ralph Nader was one of Gates’s most prominent supporters. Gates referred to the prevailing economic regime as “money on autopilot.” It is time that we design an economy where we confront our responsibility deficit, where we disable the autopilot machinery and replace it with an “eyes wide open” ethos and regime of law and corporate governance that manages consciously, ethically, and with responsibility.

Recent Publications

- January 1, 2021

- Published Articles, The New Republic

- June 1, 2020

- Challenge Magazine, Published Articles

- March 25, 2020

- Published Articles, The New Republic

- October 7, 2019

- Challenge Magazine, Published Articles

- April 19, 2019

- Published Articles, The Financial Times

- August 30, 2018

- Published Articles, The New Republic

Christopher (Chris) Mackin is the founder and President of Ownership Associates in Cambridge, MA and a partner at American Working Capital. He also serves as a Ray Carey Fellow at the Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations in the Rutgers Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing.

Recent Lectures

At the Harvard Law School Forum: BUILDING WORKPLACE DEMOCRACY: THE EMPLOYEE EQUITY LOAN ACT – October 12, 2018

Slides – Building Workplace Democracy – The Employee Equity Loan Act

All Recent Activity

- The New Republic – A Pandemic Dividend for Every American January 1, 2021

- Challenge Magazine – Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis, Public Policy and Corporate Governance Implications June 1, 2020

- The New Republic – Toward an Economic Democracy March 25, 2020

- Challenge Magazine – Encouraging Inclusive Growth: The Employee Equity Loan Act October 7, 2019

- Financial Times – Sovereign Wealth Funds Must Choose a Different Path April 19, 2019

- At the Harvard Law School Forum: BUILDING WORKPLACE DEMOCRACY: THE EMPLOYEE EQUITY LOAN ACT – October 12, 2018 October 12, 2018

- 1985 September 26, 2018

- The New Republic – Silicon Valley and the Quest for a Utopian Workplace August 30, 2018

- More About Christopher August 27, 2018